Physicist Brian Lee has a special interest in Native American pictographs and petroglyphs. And through his adventures in Southwestern states, he's photographed the remains of fascinating etchings and paintings, many of which reside in remote regions and are often defaced by vandals. He shares his knowledge of the fading artwork of bygone civilizations.

This Native American painting intrigues us. What’s the story behind it?

That pictograph panel — archaeological human-made markings on natural stone, aka rock art — was found (rediscovered) by another photographer on Flickr, Randy Langstraat, in 2011 — I first saw it on Randy’s photostream. He called it the “Unexpected Panel” because he was so surprised to find it in a remote location in the American Southwest.

Why are the specific locations of pictograph panels rarely disclosed?

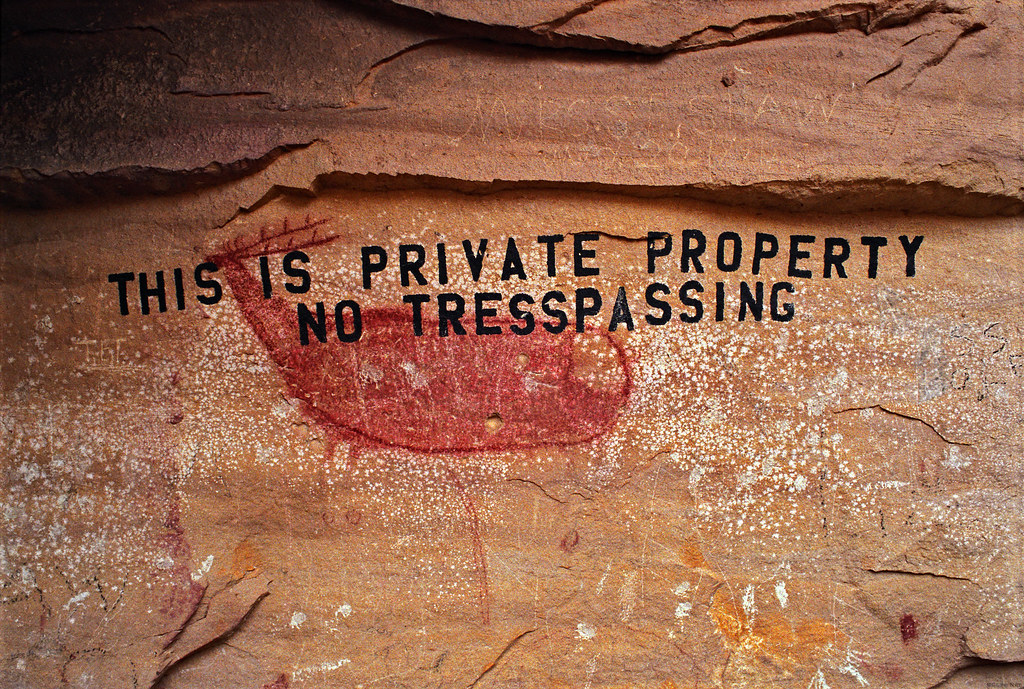

Most people who visit these panel sites are respectful, but there are always some people who aren’t right in the head — and it only takes one. A few years ago, someone started visiting many of these panels and carving their initials into them. Someone else vandalized several sites with shotgun ammo.

There’s an entire Flickr group with photographic examples of vandalized panels:

One of the most heartbreaking examples is in Nine Mile Canyon:

Sometimes people even try to steal panels, although this usually ends up just destroying the rock art.

Do we know much about the meaning and history of them?

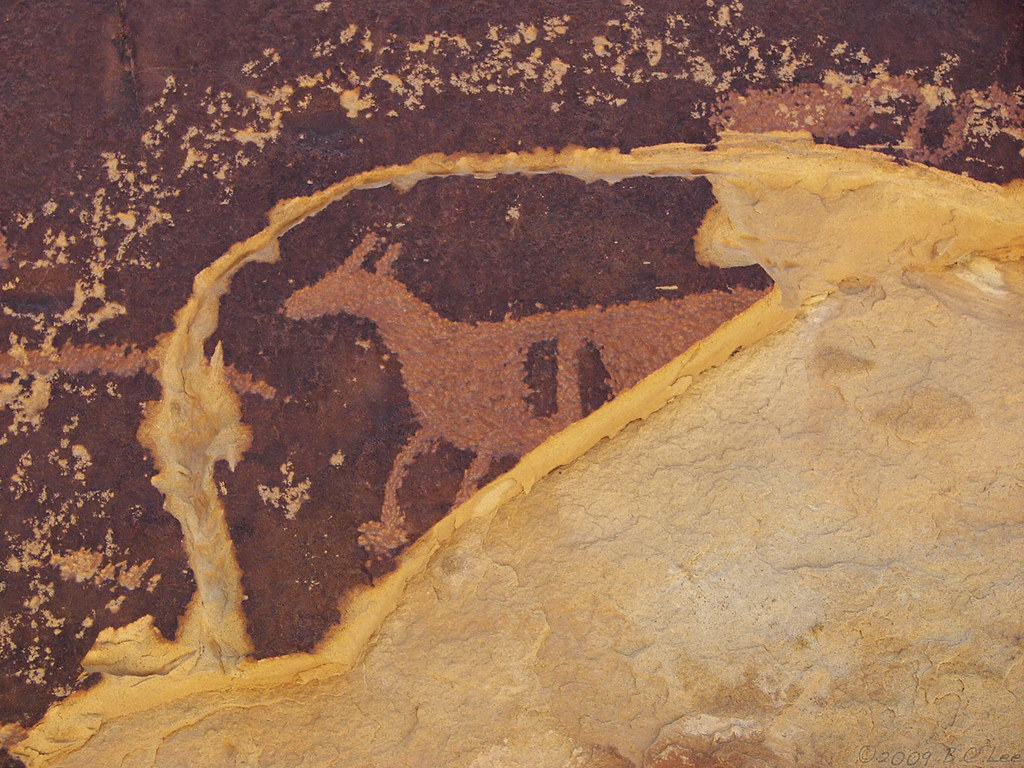

A lot of my photos, a lot of my interest, is in a style of rock art called “Barrier Canyon Style” a name coined by Polly Schaafsma who was the first person to recognize them as distinctive from much of the other rock art in the Southwest. These sites with this style are rare compared to other rock art in the region (mostly Utah). The name comes from several panels along Barrier Creek in what’s now called Horseshoe Canyon, a remote section of Canyonlands National Park added to the park in order to protect these same panels.

Barrier Canyon Style works are most often painted (pictographs) although a few are pecked into the rock (petroglyphs), and many painted figures also include pecked details. Some of the paintings have large, ghostly figures — I’ve seen one that’s over 10 feet tall — some with fantastical features that people compare to owls, insects, or aliens. Tiny works are often incredibly detailed, as if painted by a toothpick. There are “gallery” sites with several panels where all of these can be seen, such as the Great Gallery in Horseshoe Canyon, Thompson Canyon, or Buckhorn Wash.

It’s believed these works were created during the Archaic period by hunter-gatherers. The region has been occupied since at least 8,000 years ago, and there’s evidence arguing the paintings are 1,500 to as much as 8,000 years old. During this time, before agriculture had been introduced to the region, it was sparsely populated (which combined with age is perhaps why there are only a few hundred Barrier Canyon Style panels). It’s hard to be more precise than that since it’s difficult to date the panels directly, and there’s a selection effect — some of the paint contains organic binders, and that can be carbon dated (assuming someone’s willing to let you remove some of the paint, which they usually aren’t!). But over time the organic part of the paint, the paint itself, wears away. The red ochre used for the most common red pigment, a rock rich in hematite (iron), is very good at staining sandstone, and the red stains remain long after the paint itself is gone. Those panels with the original paint gone, presumably the oldest, would be impossible to date directly. The evidence then mostly comes from indirect methods — carbon dating items (like charcoal from fire hearths) found beneath panels, or unfired clay figurines in similar styles found in the same areas as the panels. Those items generally point to a range of dates from 3,000 to 8,000 years old. Direct dates from the pigments tend to be more in the 1500-3500 year old range, but as I say there may be a selection effect where only the newest panels can be dated directly.

Are there specific characters (deities, leaders, symbols, etc.) depicted in them?

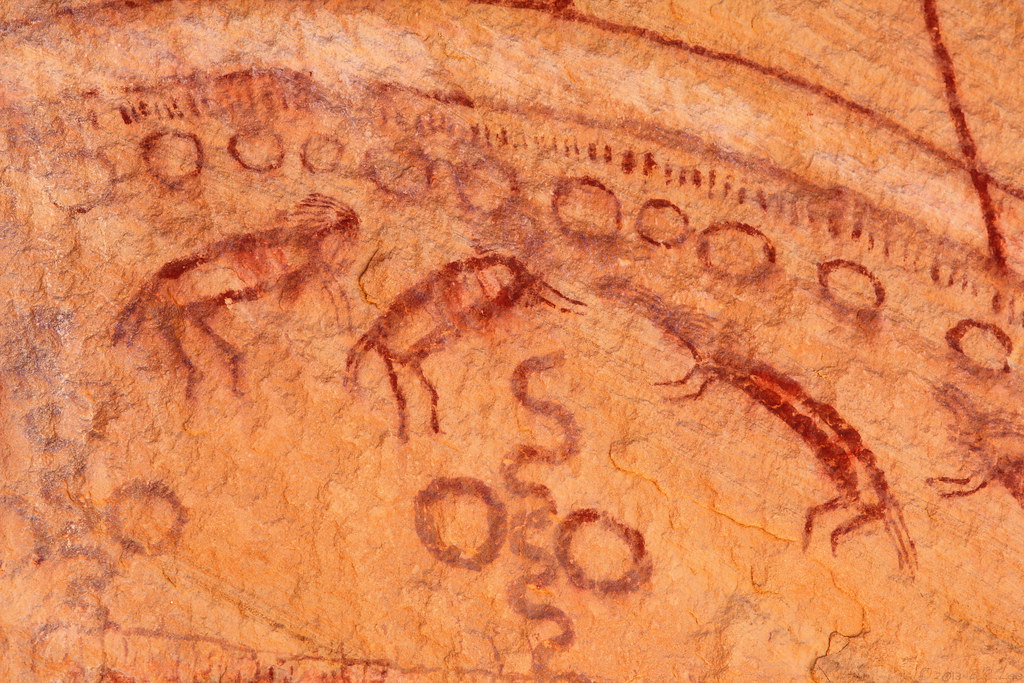

This is a tricky question, when we get into details like that the real answer has to be that no one really knows. With that caveat, I’d say yes — there are several recurring characters that show up. One for instance is a horned serpent, it appears in many panels. But what does it represent? A Cherokee friend of mine saw one of my photos and said she thought it was Uktena. Other people wonder if it’s related to Quetzalcoatl. Neither of those have sheep heads though, and some of the Barrier Canyon Style depictions have what appear to be ears in addition to very sheep like horns. In one panel there’s a humanoid figure with a sheep’s head with a snake tongue. Maybe all these figures are related, but how can we know? There are several more examples, not just specific features but specific characters that seem to reappear.

If these panels were created over the course of thousands of years, it’s possible even the original meanings were lost, but the same characters repeated by later generations. There are Barrier Canyon like details in even more recent Fremont (agricultural contemporaries of the Anasazi) and historic Ute rock art — later artists see the earlier works and are influenced by them whether or not they understand them. David Sucec, an art historian who studies and documents Barrier Canyon Style rock art, has talked about dealing with these uncertainties, and the complex difference between people and style. If we build a building today with Roman columns, that doesn’t make it a Roman building, but it is a Roman style we’re using. Artists borrowing from earlier artists can make this all very complicated, especially when those people didn’t have a written language.

What’s the most fascinating thing you’ve learned about them through your photographic explorations?

My wife and I first saw a Barrier Canyon Style pictograph on our honeymoon 20 years ago, in Thompson Canyon (a short drive off I-70):

At that time we knew nothing of what I’ve mentioned above, nothing about the archaic peoples of Utah, almost nothing about the archaic peoples of the land we live in. I knew of the ancient Puebloans (the Anasazi), but even that seems like relatively recent history to me now. Thousands of years ago, there were hunter gatherers in Utah creating fantastic works of art that still fascinate us today.

On the photographic side, I’ve learned a lot just trying to photograph these often damaged and faded panels. I do tend to lean much more toward documentation than spectacular photography (compared to someone like Randy for instance!). And maybe because I’m a scientist and much of what I’ve done for a living since grad school involves image processing, I do get into that end of things. I’ve learned a lot about using Photoshop to bring out details and contrast without destroying information — typical contrast enhancement techniques like unsharp mask actually selectively blur images in a way that makes them look better to our eyes but can destroy details. Some of that stuff can be counter productive depending on what kind of detail you’re trying to bring out. Selective color processing gets even more tricky. Something I’ve used a lot recently is DStretch, software developed by Jon Harman to apply decorrelation stretch color remapping, originally developed for satellite imagery, to archeology.

On our most recent trip to Utah, we visited mostly very faded panels what are difficult to make out by naked eye. What remains can be amazing after processing. A couple of examples of panels that you could walk right past if you weren’t looking carefully:

In this case for this panel, I’ve shown some examples of different processing techniques.

And this panel from our last trip:

What pigments were used to create them? How did they last this long?

Red and purple ochres appear to be the most commonly used pigments, and are easy to find in the same canyons as the art. But better preserved panels also have white, green, blue, black, and yellow paint. As I’ve said the ochre is very good at staining the sandstone and can leave a stain that lasts much longer than the pigment itself, many of the panels were probably much more colorful at one time. There are some panels where it’s clear they used as much yellow as red, but the yellow is nearly invisible to the naked eye today. It’s possible red wasn’t even really the most common color, just the one that lasts the longest.

In addition to the staying power of the red pigment, much of this area is dry, and in protected alcoves the paintings and other artifacts can last for thousands of years. I went to grad school in Michigan, and the only rock art I saw there was only discovered after a forest fire burned away the moss and vegetation that covered it. In the Southwest, it’s dry enough that they occasionally find things like mummified giant ground sloths that died out at least 10,000 years ago.

How vulnerable are they now? What’s being done to preserve them?

They’re very vulnerable: The only things that protect many of these is that they’re remote. Some of the well known sites, especially within the national parks, are developed and carefully watched. The interpretive signs can help educate people to the importance of these sites. And every time I’ve been to the Great Gallery in Canyonlands National Park, there’s been a ranger there watching over people. But there are many more sites in remote canyons where all we can hope of that the wrong person does’t stumble across them. It’s hard to know what to do to protect them, Utah can hardly afford to plant a police officer or ranger at each site, although they do what they can — while exploring back country once I met a sheriff who was patrolling known archaeological sites. But he can’t do that every day, he said mostly he could just monitor for damage and record it once it’s happened. The good and bad thing about the Internet is that once a new site is found, even if no information is shared about it other than photos, some people eventually figure out were it is. It’s becoming impossible to stick with the strategy of protecting the sites through obscurity. I think our only hope is greater education, education about what and who was here before the most recent group of settlers and why it’s important.

What’s your experience like on Flickr in regards to connecting with other rock art aficionados?

It’s been fantastic. I started posting my photos of rock art on the web back in the ’90s when the Web was young, and certainly I met a few people that way. I started using Flickr simply because the notes and mapping functionality allowed me to go into more detail much more easily than I could on the web server I was using at the time. Now I can note those recurring characters, I could link to closeup shots or sets, I could see what other people had found in the same areas. The social side of it came as a complete surprise — a whole community of photography enthusiasts with similar archeological interests developed on Flickr. I learned much more from other people than I ever had with my own webpage, and I came to know many people I’d never have met otherwise.

Thanks, Brian, for sharing your insight about Native American rock art.

Check out Brian’s photostream for more of his photography, and explore more photos related to this subject in the Native American Cliff Dwellings, Petroglyphs and Pictographs group.