Meet Great Basin School of Photography co-founder Jeff Sullivan, winner of the 2011 International Astronomy Photographer of the Year "People andSpace" special prize. Jeff is author of the photographers' guidebook, "Photographing California - Vol. 2 - South", and has been named a Top 100 Travel Photographer in the World. A dark sky advocate and avid time-lapse astrophotographer, his web site is ranked as a Top 30 Astrophotography Blog. A Canon and Nikon user for decades, his background includes a Computer Science degree from U.C. Berkeley and professional work in the field of digital imaging since 1984.

1. Please introduce yourself. Who are you? What do you do? How long have you been into photography?

I am one of the co-founders and instructors at Great Basin School of Photography, with my wife, Lori Hibbett. We’ve been leading workshops together for a dozen years, but our interest and experience in photography goes back decades. I took a darkroom photography class in eighth grade, and upon graduating from U.C. Berkeley with a computer science degree, I went straight into digital imaging, a couple of decades before digital cameras became generally available.

2. In one sentence, please describe what you captured in this shot.

The water table in Badwater Basin can be very close to the surface of the salt playa. That’s how these polygons form: salt-laden water rises up between cracks in the salt in capillary action, until it dries and deposits its minerals at the surface. The polygons grow as more salty water pushes up the salt above and deposits more salt. Occasionally, excess water floods the basin, creating a temporary lake, until heat and wind evaporate the water, leaving the rock salt polygons raised above the otherwise flat salt surface.

3. Why did you select this photo to share?

This sunset is one of my best examples of pre-visualization, an image that I anticipated before I arrived onsite. I knew that the salt flats were flooded, and when I looked up the sunset forecast, it was clear that we should skip our planned shoot on Mesquite Flat sand dunes and head to Badwater Basin instead. I envisioned a sunset reflection shot superimposed on the salt polygons of Badwater Basin, and the conditions and outcome didn’t disappoint!

4. What style of photography would you describe this as and do you typically take photographs in this style?

I try to reproduce what I perceive onsite, which is distinct and different from what a camera captures. Our eyes capture different exposures at every point they sample, including in bright highlights and deep shadows. Our brains create a balanced image, retaining the perception of contrast between light and dark areas, despite our pupils brightening or darkening the light that falls on our retinas. My photographic process often similarly captures brighter and darker exposures to make available a broader range of light than a single RAW file can capture.

I don’t always need or use the extra exposures, but having them available produces more successful results in the most dramatic lighting conditions, exactly when the cost of missing a shot to blown highlights or black, featureless shadows can make or break your shot. Few people drive a car without insurance, or own a house without insurance. I can’t imagine risking the time and expensive of travel, and unique and dramatic sunrises and sunsets that will never be repeated, on a single exposure that technically cannot contain the 17 stops of light that can be present. It seems to me that a pro should shoot for results, not for the weird ego trip of “I (sometimes) get my images in one shot (when the scene doesn’t involve too great of a range of light for a digital sensor)!”

5. When and where was this photo taken?

This was the first shoot of our Death Valley Winter Light photography workshop in December 2019. We’ve found that winter tends to be the best time to find water flooding Badwater Basin, and with lower heat, less wind, and rain showers to refresh the pool, this time it remained for five weeks!

6. Was anyone with you when you took this photo?

I think we had a small group of 7 or 8 with us on this workshop. We prefer to run smaller workshops, since we can give clients more attention.

7. What equipment did you use?

I captured this image on a Nikon D850 with a Nikkor 17-35mm f/2.8 lens.

8. What drew you to take this photo?

Death Valley is such a dry place, passing storms that create stunning sunsets are fairly rare. Combine that with the uncommon conditions of flooded Badwater Basin, and you have the opportunity for some unique and compelling shots.

9. How many attempts did it take to get this shot?

I initially decided to leave my camera capturing a sequence of photos that I could later assemble into a time-lapse video (see below). This freed me up to check on the workshop clients and make sure that they are capturing the images that they want. Lori was doing the same.

When I got back to my camera, I switched into Automatic Exposure Bracketing and switched my attention to capturing the range of exposures required to create greater fidelity still shots, like this image. Sometimes we even use exposure bracketing at night, and we stayed until the stars came out, to capture their reflection in the water. With film cameras it was important to capture the best possible image in camera, in one exposure. Starting in film, I had that same bias. When I entered digital imaging, it was clear that we could transcend the severe limitations of that model, and the poor range of a 12-bit (later 14-bit) RAW file. I shoot in the Sierra Nevada, the mountains Ansel Adams dubbed the “Range of Light”. Of course I want to capture and show as much of the literal range of light as I can, and in engineering terms, improve the strength of the signal (subject) over the noise.

10. Did you edit this photo?

As Ansel Adams once said, “You don’t take photographs, you make them”. He adjusted what the camera captured with filters, chose what the exposure would include, and he adjusted the results via many hours in the darkroom, often re-interpreting an image months or years later. Similarly, I want to convey my experiences in special places, not serve as a sort of “walking web cam in hiking boots”, producing low fidelity JPG images. Outside of editorial work, photography is rarely a “take what you get” medium.

I fully adjusted my middle exposure in Adobe Lightroom, pasted those adjustments into the adjacent exposures, then combined multiple exposures into a 16-bit TIFF file. This creates a higher quality master to work on. I made standard photographic adjustments from there: brightness, contrast, a little dodging and burning to direct the viewers’ attention.

11. What encouraged you to share this photo online and with others?

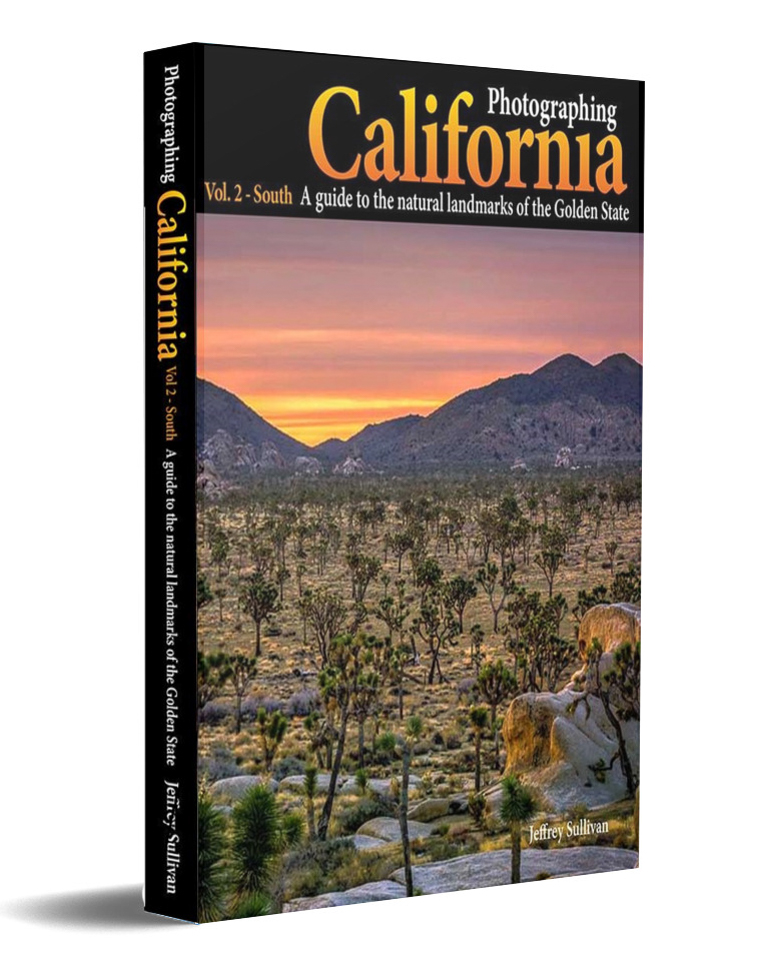

This is what I do, share places and moments in nature with others. Lori and I spent four years researching my 320-page guidebook, “Photographing California Vol. 2 – South, A guide to the natural landmarks of the Golden State”. Now we’re taking photographers to those places and helping them arrive in the best places for the best conditions and light. And for people that are interested, we share our exposure process and post-processing techniques, so they have the greatest possible control over their results. It’s rewarding seeing people expand their portfolio of skillsets over time, and develop their own style.

12. Did you learn anything in the process of taking, editing, or sharing this photo?

Sometimes I’d get a comment that the image was “fake” or “oversaturated”. I don’t use Photoshop, and if I ever touch the saturation slider, I tend to desaturate. A lot of people are viewing images on their mobile phones these days, and I did notice that certain images sometimes appear too colorful on a mobile phone. Perhaps manufacturers feel that they sell more phones in stores if they manipulate the color on their displays. I think another factor is that most people don’t get out much, so they don’t experience much of the range of what nature can deliver. Even being out a lot, more often than you might expect I get shocked by the sheer spectacle of what I’m seeing!

“Badwater Basin Time-Lapse” by Jeff Sullivan

It can be tempting to dumb down a resulting image to avoid the discomfort of getting accused of faking something. But when we experience such a natural event, one that is truly startling, one that surely no one is going to believe later, I mark that moment in memory by saying it out loud. “No one is going to believe this!” I point out to our workshop clients that since we can’t believe what we’re seeing in that moment, if everyone believes their resulting images later, they’ve failed to fully communicate and convey the experience. In other words, as photographers we can assume the challenge of trying to show people the full range of what’s out there in nature’s most spectacular moments, while daring not to dumb them down. It’s a freeing experience, fully accepting that this requires producing images for yourself, not to please others. We owe it to ourselves to not rewrite history, to not downplay the most amazing moments that nature has given us.

13. Do you remember what you had for breakfast (or lunch or dinner) the day you took this photo?

I remember that dinner had to wait until after dark. There’s plenty of time to eat on clear blue sky days. Nature photography drives and inspires me; calories just sustain me.

14. What would you like people to take away from this photo?

My eighth grade interest in film photography eventually led me to bring other photographers to this exotic location in stunning conditions. My interest in NASA’s Apollo and Space Shuttle programs led me to night photography and teaching that. To pursue my full potential, I have to do what I determine is the right path, and practice my ability to ignore naysayers. Would you do anything new or different with your photography? Are there other areas where we can be truly free to pursue whatever potential we see for ourselves? Apply that principle to your other interests, and who knows where you’ll go? Twenty years ago I took up home winemaking. Since then, I’ve planted and manage 400 grapevines. Maybe I’ll start a winery (if I can afford the licensing and irrigation fees), or go work at a winery as a retirement career. What would you like to do? Start now, and stick to it.

15. Is there any feedback that you’d like to get on this shot?

What interesting natural events and conditions do you most like to pursue? Sunsets? Moon rises? Fall colors? Wildlife?

We like to anticipate and pursue “moonbow” lunar rainbows at night in Yosemite Valley, the orange glow of Horsetail Fall backlit by the setting sun, interesting conditions in Death Valley like Milky Way shots, flooding in Badwater and spring wildflower blooms, Milky Way shots in Western ghost towns, sunset moon rises at Mono Lake, and astronomical events like comets and eclipses. Perhaps we should do more aurora borealis shooting (we’ve seen it as far south as Nevada), spend more time with Yellowstone geysers and rutting elk.

What other repeatable natural spectacles are worth years of exploration and pursuit?

16. How can anyone reading this support your work?

Check out our photographers’ guidebook, “Photographing California – Vol. 2 – South” (buy a copy, give it as a gift, tell others about it).

Buy a print on SmugMug or through our Flickr Prints shop. Join us for a photography workshop! Find us on social media, and like, comment, and share our posts: Facebook,YouTube,Twitter, that helps our web site get found on Google searches. We’re essentially in the U.S. travel industry, which has been heavily impacted over the last four years. Every little bit helps. Thank you so much for your support!

Not a Flickr member yet? Sign up today to join our community of photographers and find your inspiration.