By virtually any definition, Rick Guidotti had it all. As an in-demand fashion photographer in the 1990s, he routinely shot supermodels like Claudia Schiffer and Cindy Crawford. Based in New York City, he also lived in Paris and Milan, working for high-profile clients like Yves Saint Laurent, Revlon, and Marie Claire.

But beneath the glamour, he was routinely frustrated by the narrow and predictable standards of beauty his field forced upon him. “I was always told who was beautiful,” he explains. “As an artist, I didn’t only see beauty on the covers of magazines. I saw beauty everywhere.”

Everything changed one afternoon in Manhattan. Rick left his studio after a casting session for Elle Magazine, and as he walked down Park Avenue, he caught a glimpse of a pale young woman waiting for the bus. “I [had] never met a model that looked like her,” he says. Although he didn’t manage to catch up to her before she got on the bus, that glimpse forever altered the course of his life and career.

Although he knew virtually nothing about albinism, Rick recognized its telltale lack of pigmentation in the girl he saw. She had very pale skin and virtually white hair. He thought she was gorgeous. Captivated, he ran down a few blocks to Barnes & Noble to learn more. But as he began perusing medical textbooks dealing with albinism, he was shocked by the depressing and dehumanizing images he saw. Most were clinical photos of patients naked, up against the wall in doctors’ offices or cancer wards, with black bars across their eyes. Or they were extreme close-ups of giant red eyes. “These were images of diseases. These were not images of people,” he recalls the horror he felt. “And I thought, ‘Where is the photograph of this gorgeous kid I just saw waiting for the bus?’ She wasn’t there.”

Rick decided he wanted to shoot photos that showed the beautiful and human side of people with albinism. He soon discovered NOAH (National Organization for Albinism and Hypopigmentation), a support group for people with albinism. He called them, excited about the possibility of photographing other young people with the unique beauty he had seen that day on Park Avenue. However, NOAH’s initial response was unenthusiastic. Every photo shoot or magazine article that they had agreed to support in the past had turned out to be exploitative or outright negative, and they weren’t about to put the young people in their organization through more humiliation. But Rick was persistent and eventually gained their trust. He had a vision to create images that would counteract the negative and clinical portrayals of people with albinism.

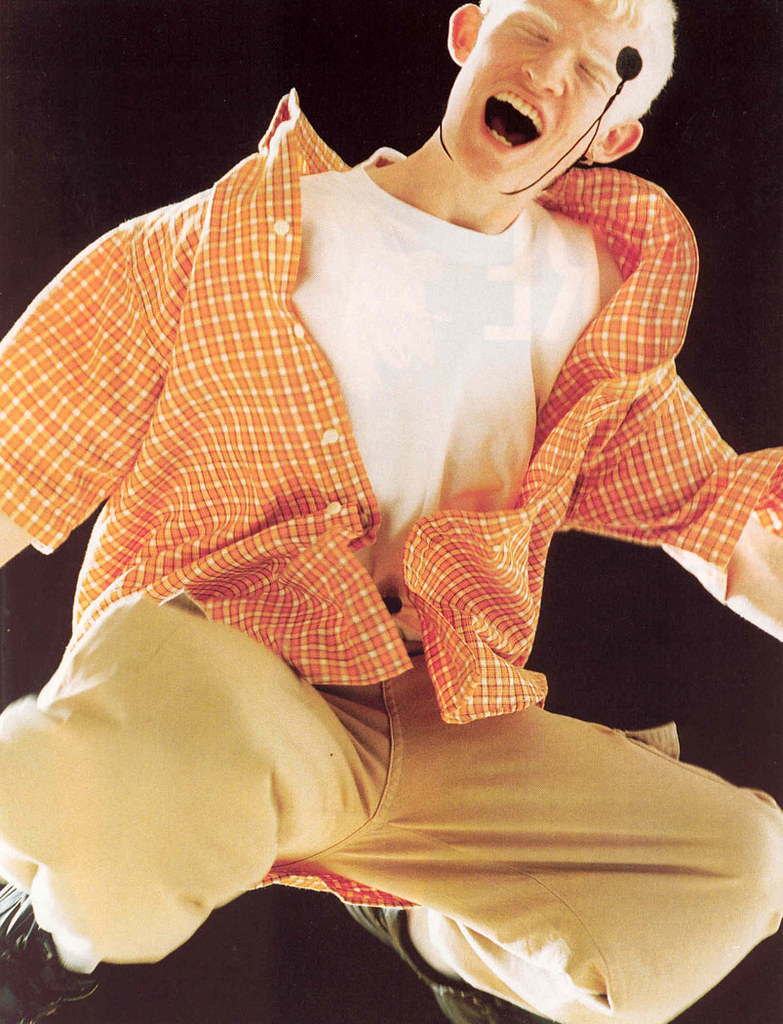

The first young woman Rick photographed as part of his partnership with NOAH was Christine. Although he recognized her as a beautiful teenager, she came into his studio with her head down, shoulders hunched, avoiding eye contact. After a lifetime of merciless teasing in school, he explains, “This kid had zero self-esteem. I thought, ‘Oh, she’s so vulnerable, how am I going to photograph this kid?’” Undeterred, he decided to shoot her with the same style and approach he had used with Cindy Crawford the previous day. “The fan and the music went on, and I grabbed a mirror. I held the mirror up, and I said, ‘Christina, look at yourself. You are magnificent!’ And this kid saw it! She saw this image and she just went, boom! She just exploded with this smile that literally lit up New York City. That’s when I realized how powerful the camera was as a medium, to present self-esteem, to present self-acceptance, and to see beauty.”

That first series of photos of people with albinism became a cover story in Life Magazine and set in motion a new chapter in Rick’s career. People from around the world began to call. Other magazines began running the images. Invitations began pouring in to photograph, to speak, even to help start support groups, and he began a globetrotting advocacy for people with albinism that continues to this day.

Rick also created the nonprofit Positive Exposure in 1998 and ultimately left fashion photography behind. He now photographs and advocates for people not only with albinism but also with a wide host of genetic conditions and chromosome anomalies. Positive Exposure engages in numerous visual-art initiatives to humanize, encourage, and inspire people living with these conditions, including public exhibitions around the world, gallery shows, videos, public speaking, and even working with medical students. “It’s about going into medical schools and presenting these images to health care providers in training, creating that philosophy that it’s not what you’re treating, it’s who you’re treating,” Rick explains.

Positive Exposure’s story is now being told in a documentary titled On Beauty, produced by Kartemquin Films and directed by Joanna Rudnick. The film has won numerous festival awards and premieres in theaters this month.

Rick views his work with Positive Exposure as a continuation of the same passion that first led him into fashion photography. “From day one, when I picked up my camera and started shooting, it has been about beauty. People say, ‘Oh, you went from shooting supermodels to photographing people with genetic diseases.’ I’m like, ‘Well, first of all, I’ve never photographed a genetic disease in my life. This is about people. This is about humanity. Nothing’s changed.’”

Through his photography, Rick is changing how we see people with genetic conditions. “It’s so exciting to be part of this human movement, to see beauty in difference.”

Visit Rick’s Photostream to see more of his moving portraits.

Previous episode: Photos reveal a side of cosplayers you won’t see at Comic Con

Do you want to be featured on The Weekly Flickr? We are looking for your photos that amaze, excite, delight and inspire. Share them with us in the The Weekly Flickr Group, or tweet us at @TheWeeklyFlickr.

Do you want to be featured on The Weekly Flickr? We are looking for your photos that amaze, excite, delight and inspire. Share them with us in the The Weekly Flickr Group, or tweet us at @TheWeeklyFlickr.