“This project humbles me because people entrusted me with their stories. And what fabulous stories… of young people making a difference!” – Alice W Campbell, Digital Outreach and Special Projects Librarian, VCU Libraries.

Darwyn White gazes into the camera lens.

In April 2014, Virginia Commonwealth University (VCU) Libraries launched the Freedom Now Project, a photography collection documenting the pivotal civil rights protests that took place in the rural town of Farmville, Virginia, USA, in the summer of 1963. With this project, the library looked to reach a broad audience so as to identify protesters and preserve the stories of the people who participated in these historical events.

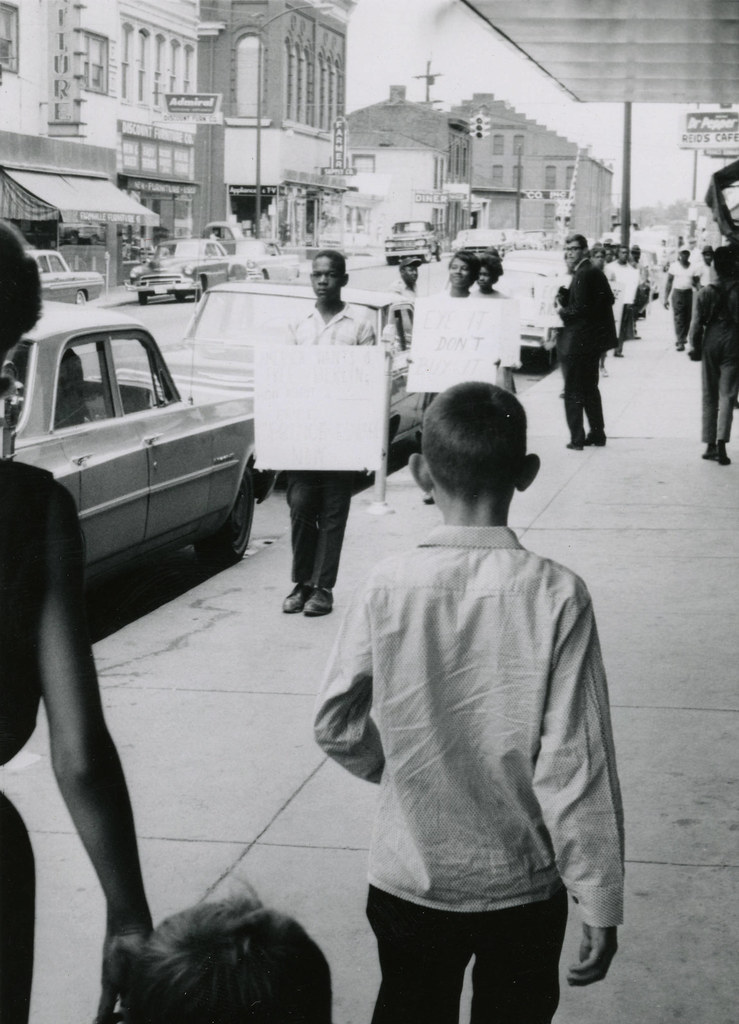

The photographs were taken to document protests conducted as part of a “Program of Action” undertaken by the Black community in Farmville, Prince Edward County, VA. Protesters demanded the end of racial segregation and the reopening of the public schools, which had been closed since 1959 as part of Virginia’s policy of “Massive Resistance.”

“Once we launched the project, the word went out like wildfire,” said Campbell, the project manager. “But, for whatever reason, community members wouldn’t add comments to Flickr. […] Instead, they called me on the telephone, and they said, ‘You have pictures of me up on your website.’ And I said, ‘Really?! Do you know any of the other folks in the photographs? Could we get together and talk?'”

The vast majority of the people in these 1963 photographs were students and pastors from the Black community pushing for desegregation, determined to speak up after four years of putting up with Prince Edward County’s government’s decision to close all public schools in defiance of court-ordered desegregation. A decision that forced more than 1,500 Black and some poor white children to miss four years of education or move in with relatives in other states—often separated from siblings and parents, and that the Kennedy administration tried to tackle by sponsoring the Free Schools project. In 1964, after a court order, the county’s public schools were finally forced to reopen.

Two boys facing each other. See photo description for sign text.

“Once public school started up again in fall 1964, the schools were largely segregated. Most of the white students stayed in the private Prince Edward Academy, while Black and poor white students went to the public school. For many more years, that was de facto segregation,” said Campbell.

Since the project’s launch in 2014, 80 people have been identified, mainly through direct community outreach. “I wanted to know more, but I couldn’t always reach people online, and I couldn’t always arrange to be with people in person. You can’t go to everybody’s kitchen, and they can’t always drive to VCU. So I printed out a number of the photos and created a scrapbook.” And the scrapbook made the rounds at choir practices and NAACP meetings in Farmville, which eventually led to more contacts and more conversations.

“This is another picture of Darwyn. And if you look, she is wearing a ring on a necklace. In my day, if you wore a boy’s ring, that meant you were “going steady,” which meant dating seriously in highschool terms. But here’s the thing: there wasn’t any high school. So who is she dating? Where did the ring come from? What did the ring mean? I don’t know. It’s one of those mysterious details that will keep you coming back again and again to look at a photo.”

The photos in this collection were originally commissioned by law enforcement, who hired at least two men to take pictures to be used as evidence in court. That evidence was never needed. “The presence of the camera–of the photographer–and of the subjects’ relation to the camera is so evident. And their relationship changes over the course of the protests [which took several weekends]”

“You’ll notice, for example, people holding their hands up to their heads. And the reason that is happening is because they’re trying to frustrate the photographer who’s taking pictures for evidence. But after a while, some of them start to push back and they pose for the camera, and you can really see the personality of these teenagers. It’s so wonderful.”

The collection, available and easily navigable on Flickr, tells a story that visitors can experience in as much depth as they choose. Just browsing the Albums page or zooming in to examine the photos closely is a learning experience in itself. Still, the information and links included in the photo descriptions offer a more in-depth experience for those who want to delve into the details of this not so distant era of American history.

“One of the things I have loved about this project is that, this kind of history–these stories– are made by people like you and me. […] The details of the 1963 protests that we learned weren’t proclaimed by an official spokesman who had the microphone on the platform of the day; The Freedom Now Project succeeded through the cumulative effort of neighbors and cousins and colleagues at work getting to share their stories. And it was a profound reminder for me that everybody’s story, everybody’s perspective can be a little different.”

March on Washington buttons.

If you enjoyed this story, please consider giving the Freedom Now Project account a follow or leaving a comment. The digital collection is in the public domain, and the photos have been used, with attribution to the VCU, in various books, documentaries, and exhibits.

Know anything about these mystery photos? Leave a comment and get in touch! And if you’re interested in the work our Commons institutions are doing, please consider joining the public Flickr Commons group for more conversation around other projects like this.