Zeb Andrews is a pinhole photographer, taking stunning, lensless photos through a single aperture. “Pinhole photography allows me to view the world differently,” Zeb tells The Weekly Flickr. “We see the world in fractions of a second. And the fact that a pinhole camera captures a span of time is already vastly different from how we see things. So every time I take this camera out, it’s like I’m putting on a new set of eyes.”

Zeb, who is from Portland, Oregon, picked up his first pinhole camera in 2004, and he describes the simplicity of making one. “Building a pinhole camera is just a matter of finding something you can make light-tight. You can make them out of oatmeal containers, trash cans, minivans — anything. You take a box and cut a little square window, an inch or so, on one side, cover that with a little piece of aluminum foil, and then you poke a hole in it with a sewing needle. And then it’s just a matter of loading that box with film or paper, and you’re ready to go.”

Zeb started shooting pinhole pictures for fun; he says, “I didn’t expect it to go anywhere. I just liked taking out this box with a hole and seeing what happened when I tried to take pictures with it.” But over the years, his work resulted in numerous gallery showings and a profile on Oregon Public Broadcasting’s Oregon Art Beat, a local arts TV series. After his story was released to national syndication, he received an email from Kinda Hibrawi, a Syrian-American painter who helps run the nonprofit Karam Foundation, asking him to teach pinhole photography in Turkey at Zeitouna, a mentorship program for at-risk Syrian children. “It really wasn’t a question of whether I was going to go or not, it was just too good of a cause to pass up,” Zeb says.

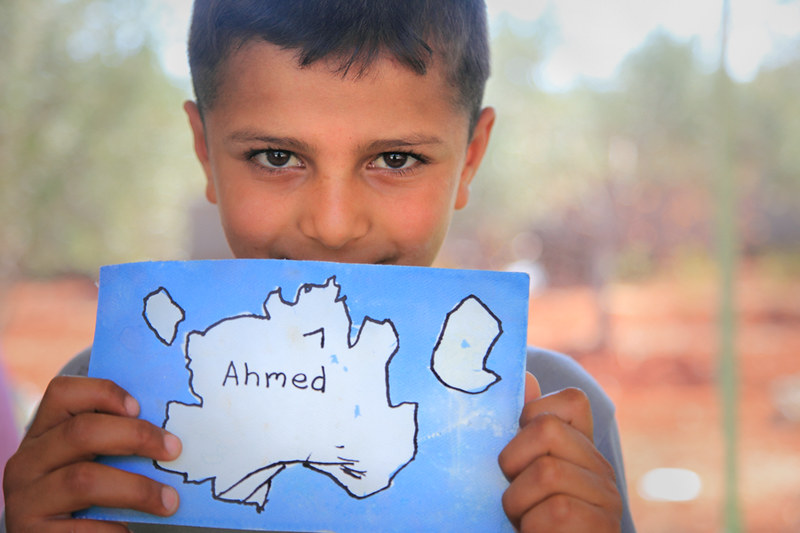

In June 2014, after raising money for his trip on the crowdfunding site Indiegogo, he arrived at the Al Salam School in Reyhanli, Turkey, on the border with Syria. For four days he taught pinhole photography to about 400 displaced Syrian children, ages 5 to 17, who had fled their native country because of the ongoing civil war. Some were in Turkey legally, others had been smuggled across the border; some had lost their families or were living in squalid conditions. With limited means, Zeb taught the basics of pinhole photography, using cameras made out of cardboard boxes, and converting a basement bathroom into a makeshift darkroom. “I was particularly struck by how resilient these kids were,” he says. “It is a pretty awful situation in Syria, and they were so inviting, so accepting, and so enthusiastic. It was hard not to be inspired and moved by that.”

Initially, the children seemed uncertain about taking pictures with a cardboard box. However, they quickly began to enjoy the unique and simple form of pinhole photography, gravitating toward taking portraits of what was important to them — each other, something Zeb hadn’t expected. With the younger kids, Zeb showed them how to make cyanotypes, or sun prints. “One girl wrote ‘Syria’ in giant block letters across her transparency, and then around the bottom of it she covered it in this dripping pool of blood,” he recalls. “In this instance, you are giving these children an outlet for what they’re thinking and feeling, and you had some pretty harrowing things coming out of these kids.”

“It’s easy to become a little cynical and jaded, and think that with big problems like in Syria, there’s nothing you can do about it,” Zeb says. “You’re just one person. But there is something you can do about it, and it doesn’t have to be a big thing, you can do little things and they can have a big impact.”

For Zeb, the time spent and the money raised to travel 7,000 miles were well worth the effort. “Some people might say, well, fundraising for four months to travel halfway around the world to teach pinhole photography is a lot, but when you look at it compared with the impact it had, and how it changed these kids’ lives, hopefully, it wasn’t that big of a thing to do.”

Visit Zeb’s photostream to see more of his photography.

Previous episode: Powerful photos tell foster children’s stories