Documentary photographer Elvert Barnes has been covering demonstrations, community events, and protests since the early 90s. His extensive portfolio includes photographs of various equity and justice-seeking social movements—from the March on Washington for Lesbian, Gay and Bi Equal Rights and Liberation of 1993 to the post–September 11th anti-war movement; from the March For Our Lives rally in 2018, to the most recent Black Lives Matter demonstrations.

For the past three decades, Barnes has attended every major US movement with a camera in tow and a desire to capture history through his lens. In this Q&A interview, he talks us through his work and what motivates him to keep photographing the streets of Baltimore, Maryland.

Flickr: Tell us about where you’re from, where you live, and what you do.

Elvert Barnes: I am a self-taught freelance documentary photographer who, except for a few years in NYC, have lived most of my adult life in the Washington DC area and, since August 2016, in Baltimore, Maryland. I’m a 66-year-old gay Black male. For the most part, where I live, work, and play serves as the backdrop of my picture-taking.

How did you get interested in and started with photography? And more specifically, in outdoor event photography?

While my interest in photography dates back to my childhood years, it wasn’t until my partner gave me a Minolta as a Christmas gift in 1991 that I decided to integrate my picture-taking with my writings.

Seldom without a camera, I always carried a note pad and have created a collection of writings and photo essays entitled “BLACKOUT” that in the future will be developed into books and exhibitions that reflect on my personal story as an openly gay Black man.

My focus has almost always been in street photography. I like the fact that the photographer has little control over what appears in the image. Years later, when viewing an image, so many details will have been recorded of a particular moment in time that cannot ever be again. That same focus also drives my protest photography.

Living for many years in Washington DC and now Baltimore MD, there has never been a shortage of outdoor events to photograph. A few of my favorite ongoing DC projects are the St. Patrick’s Day Parade, the Cherry Blossom Festival, Rolling Thunder, National Police Week, Gay Pride, and Sundays at Meridian Hill Park. And now Baltimore MD.

What is the role of a photographer when documenting a protest?

In earlier years, I usually documented a protest on assignment for an event organizer or news organization, which affected what and how I photographed. From the September 11th terrorist attacks through 2008, much of my protest photography was associated with the anti-war movement and anti-capitalist demonstrations in Washington DC and NYC. Since then, my protests documentation has been strictly for my archives.

As a photojournalist, my focus may be on demonstrators, police, and counter-demonstrators. As a documentary photographer, while marching down a particular street or through a neighborhood, I also turn my attention to the storefronts, buildings, spectators, street art, etc.

What are some safety precautions to take when photographing a protest, rally, march, or an outdoor event in general?

I tend to travel light. Almost always with two cameras. One camera for close-ups and another for distance shooting. I never carry a camera bag, which is too cumbersome. I have no interest in being arrested, so I take all precautions against any actions that may result in such.

Of most importance, at all times, I must be aware that as a Black male, law enforcement will not only overreact to me but so will protesters and other photographers.

Now that everyone has a camera in their pocket, what advice do you have for those who want to document a massive event?

My motto is, “you do you, and I do me.” Just don’t interfere with what and how I photograph.

What are the essential shots you’re looking to capture when photographing an outdoor event?

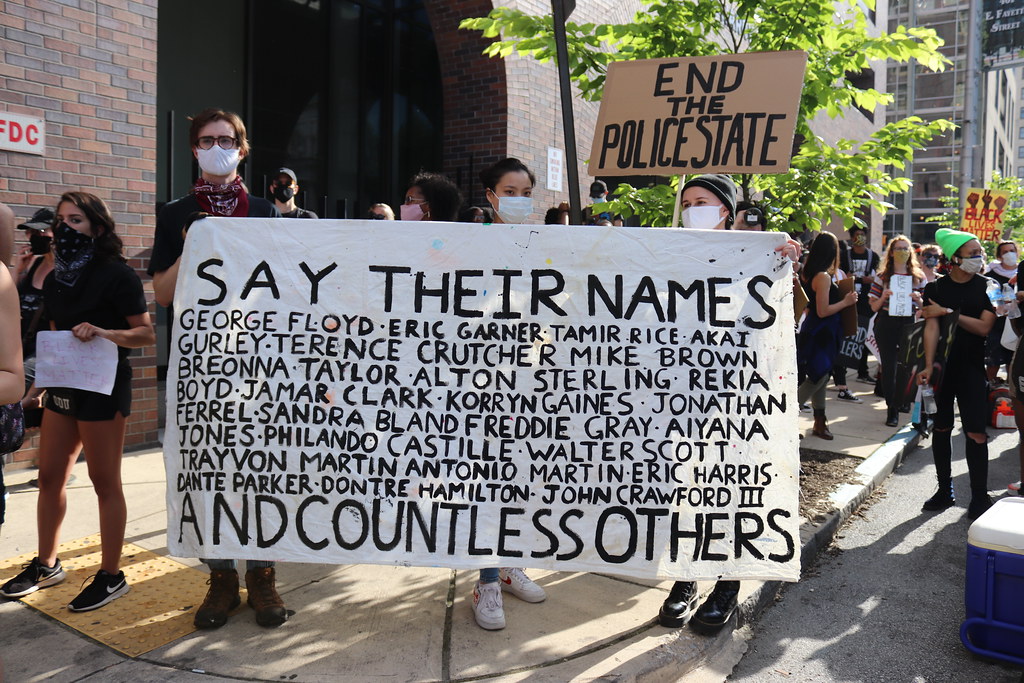

Speakers, performers, organizers, people interacting with each other, protest signs, law enforcement. Various shots from different locations and perspectives that depict the size of the crowd. Candid shots.

In your view, how can photography contribute to social justice?

Photography can play a major role in contributing to social justice as protest images often inspire others to participate in effecting change. Images from the 60’s civil rights, 70’s anti-war, and 70’s gay rights movements not only inspired generations of future activists but actually resulted in cultural and legislative changes.

Can you choose two of your Flickr photos and describe why they’re important to you?

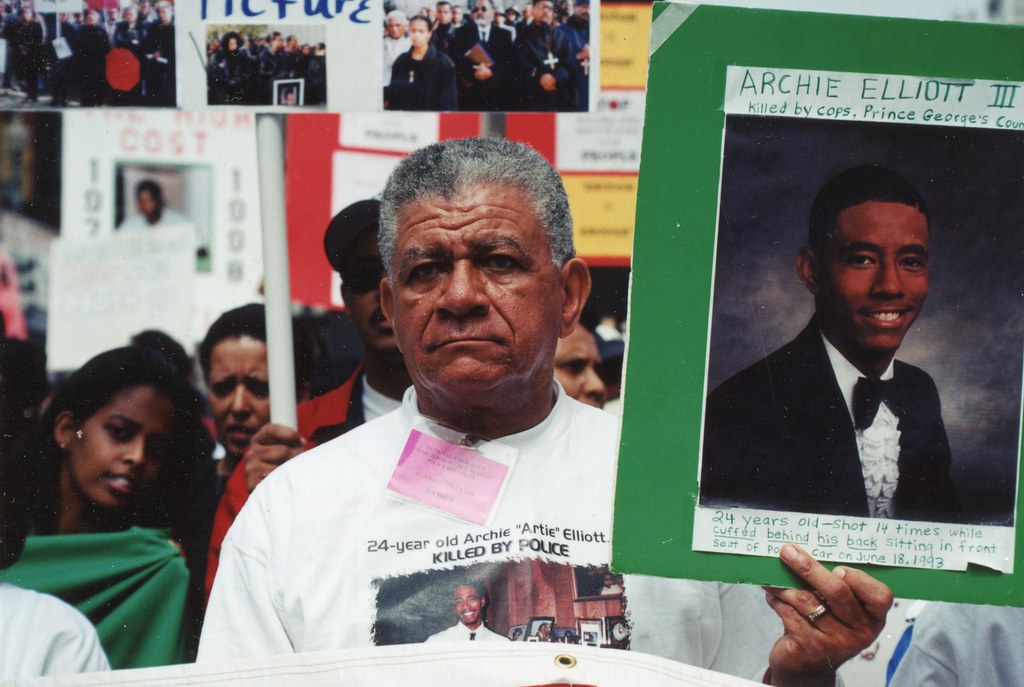

This first image was taken over Easter weekend during the April 1999 National Emergency March for Justice Against Police Brutality in Washington DC. If not the third, certainly the second year in a row, I documented an anti-police brutality protest over Easter weekend, depicting a father carrying a sign of his dead son. It still haunts me that so many Black families march against racism and memorialize their murdered sons not only over Easter weekend but also on other holidays. Every Easter since then, almost like a flashback, this picture comes to mind.

This second is of two friends, partners Mark and Ken, who have been together since 1979 and who I’ve known since 1982. Taken at the 1994 Washington DC Gay Pride Festival, I’ve always admired and respected the relationship that these two men have. This picture and similar ones that I’ve taken over the years are part of my ongoing Without Apologies project.

Is there anything else we should know about you or your work? Are you working on any projects?

As a documentary photographer, I have many ongoing projects. However, since moving to Baltimore in August 2016 and in connection with my Ride-by Shooting docu-project, which documents my travels from car, train, bus and airplane windows, my MARC Commuter Train series has been a focus. And, of course, COVID-19.

Be sure to visit Elvert’s Flickr photostream to see more of his work.